ESA’s Herschel Space Observatory has discovered a giant, galaxy-filled filament connecting two clusters of galaxies.

Along with a third cluster, say scientists, they’re due to smash together in several billion years and give rise to one of the largest galaxy superclusters in the universe.

The filament is the first structure of its kind to be observed as asupercluster begins to take shape.

“We are excited about this filament, because we think the intense star formation we see in its galaxies is related to the consolidation of the surrounding supercluster,” says Kristen Coppin, an astrophysicist at McGill University in Canada.

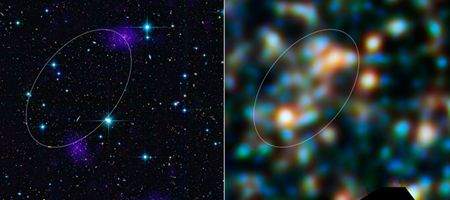

The intergalactic filament, containing hundreds of galaxies, spans eight million light-years and links two of the three clusters that make up a supercluster known as RCS2319. This emerging supercluster is an exceptionally rare object, more than seven billion light years from Earth.

Previous observations in visible and X-ray light had found the cluster cores and hinted at the presence of a filament. Herschel observations have now made the intense star-forming activity in the filament clear.

The amount of infrared light detected suggests that the galaxies in the filament are cranking out the equivalent of about 1,000 solar masses of new stars per year – a thousand times as much as our own Milky Way galaxy.

This is likely because galaxies within the filament are being crunched into a relatively small cosmic volume under the force of gravity, disturbing their gas reservoirs and igniting bursts of star formation.

The galaxies in the RCS2319 filament will eventually migrate toward the center of the emerging supercluster. Over the next seven to eight billion years, astronomers think RCS2319 will come to look like gargantuan superclusters nearby, such as the Coma cluster. These advanced clusters are full of ‘red and dead’ elliptical galaxies that contain aged, reddish stars instead of young ones.

“The galaxies we are seeing as starbursts in RCS2319 are destined to become dead galaxies in the gravitational grip of one of the most massive structures in the universe,” says McGill’s Jim Geach. “We’re catching them at the most important stage of their evolution.”