Carnegie Mellon researchers say they’ve created a computerized way of matching images in photos, paintings and sketches that’s almost as good as the human eye.

The team says its technique performed well on a number of visual tasks that normally stump computers, including matching sketches of automobiles with photographs of cars.

Most computerized methods for matching images focus on similarities in shapes, colors and composition. It’s not bad as a way of finding exact or very close image matches – indeed, it’s the method used by apps such as Google Goggles.

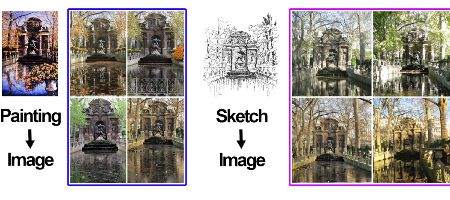

However, it’s rather less efficient when it comes to photographs taken in different seasons or under different lighting conditions, say, or in different media, such as photographs, color paintings or black-and-white sketches.

“The language of a painting is different than the language of a photograph,” says Alexei Efros, associate professor of computer science and robotics. “Most computer methods latch onto the language, not on what’s being said.”

One problem is that many images have strong elements, such as a cloud-filled sky, that may have superficial similarities to other images, but aren’t the point of the picture.

More important, reckons the team, are the unique aspects of an image. On the pixel level, a photo of a garden statue in the summer will look very different from the same statue photographed in winter. However, the unique aspects of the statue will carry over from one to the other, or from a color photo to a sketch.

The team computes uniqueness based on a very large data set of randomly selected images. Features that are unique are those that best discriminate one from the rest. In a photo of a person in front of the Arc de Triomphe, for instance, the person’s likely to be similar to people in other photos and thus would be given little weight in calculating uniqueness.

The Arc itself, however, would be given greater weight because few photos include anything like it.

“We didn’t expect this approach to work as well as it did,” says Efros. “We don’t know if this is anything like how humans compare images, but it’s the best approximation we’ve been able to achieve.”

The team says the technique could be used to enhance object detection for computer vision, and is looking at ways of speeding up the matching process.