From 1978 to 1984, the satellite was the first to orbit a point called the Lagrangian 1 (L1), which lies between Earth and the sun, where the solar wind rushes by on its way to collide with the outskirts of the giant magnetic bubble surrounding Earth, called the magnetosphere. Monitoring that wind helped scientists better understand the interconnected sun-Earth system, which at its most turbulent can affect satellites around Earth.

In 1984, it was given a new mission and in September 1985, passed directly through the tail of Comet Giacobini-Zinner, making it the first spacecraft to pass a comet. It went on to fly by Comet Halley in March 1986. From 1991 until 1997, when it was too far away for reliable communications, this satellite continued to investigate the sun.

Moving ever outward, leaving its original assignment to observe two comets, and continuing on an orbit around the sun. Now it’s coming home to visit – making its closest approach to Earth in August 2014 before it heads back out to interplanetary space.

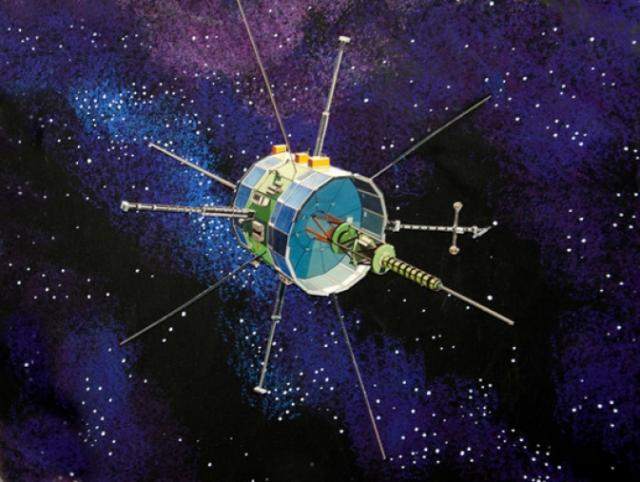

This is the story of NASA’s and the European Space Agency’s ISEE-3, the third of a set of three International Sun-Earth Explorers. ISEE-3 eventually earned the title of ICE, for International Cometary Explorer, when it was given a new mission and sent to explore comet Giacobinni-Zinner.

Signals from the spacecraft’s communication system – a constant S-band wave to show its position – demonstrate that it is still operating, but we don’t know how well. This beacon is also how we know the spacecraft is still following the same orbit around the sun, moving slightly faster than Earth.

The ISEE-3 mission was state-of-the-art when it launched. It used an S-band frequency, part of the microwave band of electromagnetic waves, for communication – at that time reserved for government air and space communications. Today, the S-band once used for ISEE-3 is now mostly used by cab driver dispatchers and very few satellite dishes even exist to communicate with it.

ISEE-3 was the first satellite to be deployed to a stable orbit point between the Earth and Sun known as L1 to measure the composition of the solar wind and magnetic fields. Today NASA has two other satellites at L1 to monitor the solar wind: ACE and Wind; and in 2015, NOAA, NASA and the USAF will launch DSCOVR to continue these solar wind measurements.

n its day, ISEE-3 sent back crucial information from a point in space where the sun’s outpouring of particles and energy can be monitored before comes into contact with Earth’s own magnetic system and halo of particles. Today, however, the technology is outmoded. Solar wind data that ISEE-3 gathered at the rate of once every 40 minutes has been replaced by instruments that are 10,000 times faster.

We owe a great debt to our old friend, ISEE-3. As the first satellite to prove the value of using stable Lagrange points for scientific research and the first to travel through the tail of a comet, ISEE-3 opened new pathways for scientific exploration. Although overtaken by advances in technology, ISEE-3 remains a testament to the scientists and engineers who conceived, launched and managed this versatile spacecraft.

Today, some citizen scientists are investigating whether it would be feasible to contact ISEE-3 for the first time in almost two decades in order to send commands to return it to L1, its original home – a daunting prospect after all this time.