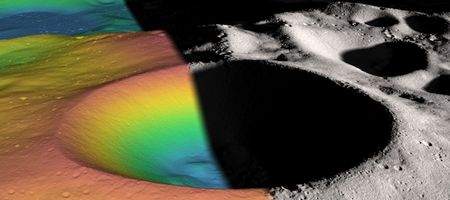

Almost a quarter of a crater near the moon’s south pole is covered with ice, scientists using NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft have found.

The team of NASA and university scientists used laser light from LRO’s laser altimeter to examine the floor of Shackleton crater. The laser measures to a depth comparable to its wavelength, or about one micron.

The crater’s floor turned out to be brighter than those of other nearby craters, which is consistent with the presence of ice.

“The brightness measurements have been puzzling us since two summers ago,” says Gregory Neumann of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“While the distribution of brightness was not exactly what we had expected, practically every measurement related to ice and other volatile compounds on the moon is surprising, given the cosmically cold temperatures inside its polar craters.”

The team also used the instrument to map the relief of the crater’s terrain based on the time it took for laser light to bounce back from the moon’s surface.

The results showed a remarkably well-preserved crater that has remained relatively unscathed since its formation more than three billion years ago. The crater’s floor is itself pocked with several small craters, which may have formed as part of the collision that created Shackleton.

Shackleton crater is two miles deep and more than 12 wide, but the small tilt of the lunar spin axis means its interior is permanently dark and therefore extremely cold.

“The crater’s interior is extremely rugged,” says Maria Zuber of MIT. “It would not be easy to crawl around in there.”

While the crater’s floor was relatively bright, its walls, puzzlingly, were even brighter. Scientists had thought that if ice were anywhere in a crater, it would be on the floor, where no direct sunlight penetrates. The upper walls of Shackleton crater are occasionally illuminated, which could evaporate any ice that accumulates.

One possible explanation is that ‘moonquakes’ may have caused the walls to slough off older, darker soil, revealing newer, brighter soil underneath. Zuber’s team’s ultra-high-resolution map provides strong evidence for ice on both the crater’s floor and walls.

“There may be multiple explanations for the observed brightness throughout the crater,” says Zuber. “For example, newer material may be exposed along its walls, while ice may be mixed in with its floor.”