Small electrodes placed on or inside the brain allow patients to interact with computers or control robotic limbs simply by thinking about how to execute those actions. This technology could improve communication and daily life for a person who is paralyzed or has lost the ability to speak from a stroke or neurodegenerative disease.

Now, University of Washington researchers have demonstrated that when humans use this technology – called a brain-computer interface – the brain behaves much like it does when completing simple motor skills such as kicking a ball, typing or waving a hand. Learning to control a robotic arm or a prosthetic limb could become second nature for people who are paralyzed.

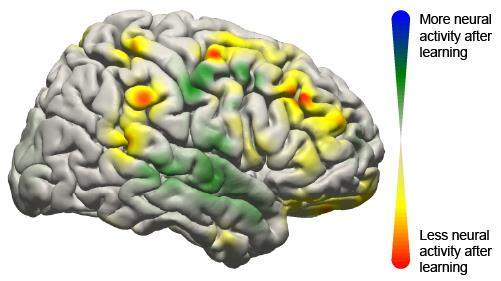

This image shows the changes that took place in the brain for all patients participating in the study using a brain-computer interface. Changes in activity were distributed widely throughout the brain.

“What we’re seeing is that practice makes perfect with these tasks,” said Rajesh Rao, a UW professor of computer science and engineering and a senior researcher involved in the study. “There’s a lot of engagement of the brain’s cognitive resources at the very beginning, but as you get better at the task, those resources aren’t needed anymore and the brain is freed up.”

Rao and UW collaborators Jeffrey Ojemann, a professor of neurological surgery, and Jeremiah Wander, a doctoral student in bioengineering, published their results online June 10 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In this study, seven people with severe epilepsy were hospitalized for a monitoring procedure that tries to identify where in the brain seizures originate. Physicians cut through the scalp, drilled into the skull and placed a thin sheet of electrodes directly on top of the brain. While they were watching for seizure signals, the researchers also conducted this study.

The patients were asked to move a mouse cursor on a computer screen by using only their thoughts to control the cursor’s movement. Electrodes on their brains picked up the signals directing the cursor to move, sending them to an amplifier and then a laptop to be analyzed. Within 40 milliseconds, the computer calculated the intentions transmitted through the signal and updated the movement of the cursor on the screen.

Researchers found that when patients started the task, a lot of brain activity was centered in the prefrontal cortex, an area associated with learning a new skill. But after often as little as 10 minutes, frontal brain activity lessened, and the brain signals transitioned to patterns similar to those seen during more automatic actions.

“Now we have a brain marker that shows a patient has actually learned a task,” Ojemann said. “Once the signal has turned off, you can assume the person has learned it.”

While researchers have demonstrated success in using brain-computer interfaces in monkeys and humans, this is the first study that clearly maps the neurological signals throughout the brain. The researchers were surprised at how many parts of the brain were involved.

“We now have a larger-scale view of what’s happening in the brain of a subject as he or she is learning a task,” Rao said. “The surprising result is that even though only a very localized population of cells is used in the brain-computer interface, the brain recruits many other areas that aren’t directly involved to get the job done.”

Several types of brain-computer interfaces are being developed and tested. The least invasive is a device placed on a person’s head that can detect weak electrical signatures of brain activity. Basic commercial gaming products are on the market, but this technology isn’t very reliable yet because signals from eye blinking and other muscle movements interfere too much.

A more invasive alternative is to surgically place electrodes inside the brain tissue itself to record the activity of individual neurons. Researchers at Brown University and the University of Pittsburgh have demonstrated this in humans as patients, unable to move their arms or legs, have learned to control robotic arms using the signal directly from their brain.

The UW team tested electrodes on the surface of the brain, underneath the skull. This allows researchers to record brain signals at higher frequencies and with less interference than measurements from the scalp. A future wireless device could be built to remain inside a person’s head for a longer time to be able to control computer cursors or robotic limbs at home.

“This is one push as to how we can improve the devices and make them more useful to people,” Wander said. “If we have an understanding of how someone learns to use these devices, we can build them to respond accordingly.”

The research team, along with the National Science Foundation’s Engineering Research Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering headquartered at the UW, will continue developing these technologies.