The mass extinction that saw the end of the dinosaurs was made worse than it might have been by the structure of the ecosystems of the time.

It was the enormous Chicxulub asteroid impact that almost certainly dealt the final blow. But, says PhD student Jonathan Mitchellof the University of Chicago, “Our study suggests that the severity of the mass extinction in North America was greater because of the ecological structure of communities at the time.”

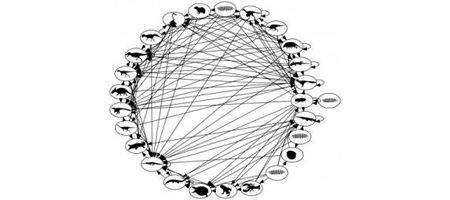

Mitchell and his team reconstructed terrestrial food webs for 17 Cretaceous ecological communities, seven of which existed within two million years of the Chicxulub impact and the other 10 from the preceding 13 million years.

They then ran the data through a computer model showing how disturbances spread through the food web and how many animal species would become extinct from a plant die-off, a likely consequence of the impact.

“Our analyses show that more species became extinct for a given plant die-off in the youngest communities,” says Mitchell. “We can trace this difference in response to changes in a number of key ecological groups such as plant-eating dinosaurs like Triceratops and small mammals.”

What they found was that, in late Cretaceous North America, pre-extinction changes to food webs – likely driven by a combination of environmental and biological factors – resulted in communities that were more fragile when faced with large disturbances.

“Besides shedding light on this ancient extinction, our findings imply that seemingly innocuous changes to ecosystems caused by humans might reduce the ecosystems’ abilities to withstand unexpected disturbances,” says Peter Roopnarine of the California Academy of Sciences.

The team’s model works through all plausible diets for the animals under study. In one run, Tyrannosaurus might eat only Triceratops, in another only duck-billed dinosaurs, and in a third a more varied diet.

“Using modern food webs as guides, what we have discovered is that this uncertainty is far less important to understanding ecosystem functioning than is our general knowledge of the diets and the number of different species that would have had a particular diet,” says Kenneth Angielczyk of the Field Museum.

The computer models showed that if the asteroid hit during the 13 million years preceding the latest Cretaceous communities, there almost certainly would still have been a mass extinction, but one that likely would have been less severe in North America.

Most likely a combination of changing climate and other environmental factors caused some types of animals to become more or less diverse, says the team. They suggest that the drying up of a shallow sea that covered part of North America may have been one of the main factors.

And there’s no evidence that the latest Cretaceous communities were on the verge of collapse before the asteroid hit.

“The ecosystems collapsed because of the asteroid impact, and nothing in our study suggests that they would not have otherwise continued on successfully,” says Mitchell. “Unusual circumstances, such as the after-effects of the asteroid impact, were needed for the vulnerability of the communities to become important.”