NASA engineers have produced the blackest stuff ever created – a material that absorbs more than 99 percent of the ultraviolet, visible, infrared, and far-infrared light that hits it.

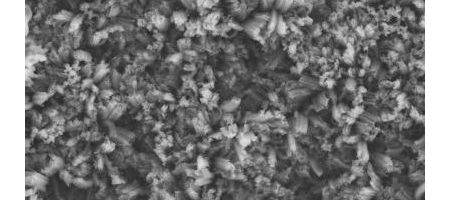

The nanotech-based coating is a thin layer of multi-walled carbon nanotubes, positioned vertically on various substrate materials much like a shag rug.

The team says it’s grown the nanotubes on silicon, silicon nitride, titanium, and stainless steel – all materials commonly used in space-based scientific instruments.

“The reflectance tests showed that our team had extended by 50 times the range of the material’s absorption capabilities,” says John Hagopian of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“Though other researchers are reporting near-perfect absorption levels mainly in the ultraviolet and visible, our material is darn near perfect across multiple wavelength bands, from the ultraviolet to the far infrared. Noone else has achieved this milestone yet.”

Tests indicate that the material’s especially useful for a variety of spaceflight applications where it’s necessary to observe in multiple wavelength bands – for example stray-light suppression, required for observing very faint light.

It absorbs 99.5 percent of the light in the ultraviolet and visible wavebands, dipping to 98 percent in the longer or far-infrared bands.

As well as having applications in astronomy, says Hagopian, Earth scientists could benefit: more than 90 percent of the light Earth-monitoring instruments gather comes from the atmosphere, overwhelming the faint signal they are trying to retrieve.

Black paint helps, but absorbs only 90 percent of the light that strikes it, and doesn’t remain black when exposed to very low temperatures.

Black materials also serve another important function on spacecraft instruments, particularly infrared-sensing instruments, says Goddard engineer Jim Tuttle – radiating heat away. This cools instruments to lower temperatures, where they are more sensitive to faint signals.