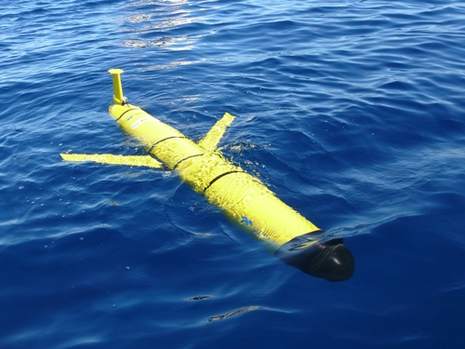

The US Navy recently tested the autonomous system capabilities of an unmanned undersea glider as the military prepares to deploy squadrons of air, surface and undersea robotic vehicles later this decade.

“Using new algorithms, the vehicle has a greater ability to make its own decisions without requiring a human in the loop,” explained Marc Steinberg of the Office of Naval Research (ONR).

“Advancing autonomy for unmanned systems allows you the ability to do things that wouldn’t be practical otherwise because we don’t have enough warfighters or communication today.”

According to Steinberg, wholly new autonomous capabilities can be achieved by incorporating fresh “intelligence” algorithms that will allow the vehicles to solve complex mission problems in complicated, dynamic environments.

To advance the intelligence of autonomous vehicles, ONR has provided funding to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and University of Southern California (USC) under the auspices of two initiatives: Adaptive Networks for Threat and Intrusion Detection or Termination (ANTIDOTE) and the Smart Adaptive Reliable Teams for Persistent Surveillance (SARTPS).

University scientists have already developed a persistent surveillance theory that provides a framework for decision-making software to maximize a robot’s collection of information over a given area.

“The ability to do surveillance that takes into account the actual conditions of the environment brings a whole new level of automation and capability,” said Dr. Daniela Rus, co-director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Center for Robotics.

“We have come up with a solution that lets the robot do local reasoning to make decisions and adjust the path autonomously without having to come up to the surface to interact with humans.”

Indeed, the scientists coded an algorithm that incorporates both the user’s sensing priorities and environmental factors, such as ocean currents, into a computer model to help undersea robots conduct surveys and mapping missions more efficiently.

“In areas where the oceanographers wanted more information, the persistent surveillance algorithm actually produces more detail,” said Dr. Gaurav S. Sukhatme, ANTIDOTE’s principal investigator and director of USC’s Robotic Embedded Systems Lab.

“The system can automatically figure out how to divide its time between areas that are more interesting and areas that are less interesting.”

Although the gliders were an ideal first test of the persistent surveillance theory and algorithm, the Navy says the software is applicable to many different machines and robots.