Last year saw a significant hole open up for the first time in the ozone layer over the Arctic.

A NASA-led team says the amount of ozone destroyed in the Arctic in 2011 was comparable to that seen in some years in the Antarctic, where a hole has formed each spring since the mid 1980s.

The stratospheric ozone layer, which reaches from about 10 to 20 miles above the ground, protects life from the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

The Antarctic hole forms when extremely cold conditions trigger reactions that convert atmospheric chlorine from human-produced chemicals into forms that destroy ozone.

While the same processes occur each winter in the Arctic, the air temperature in the stratosphere is generally higher, limiting the time frame during which the chemical reactions occur, meaning there’s generally far less ozone loss than in the Antarctic.

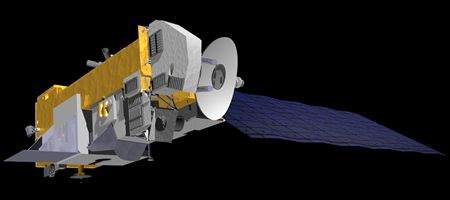

NASA examined daily global observations of trace gases and clouds from its Aura and Calipso spacecraft, ozone measurements by instrumented balloons, meteorological data and atmospheric models.

And they found that, at some altitudes, the cold period in the Arctic lasted more than 30 days longer in 2011 than in any previously studied Arctic winter, leading to the unprecedented ozone loss. They say they don’t know why the cold period lasted so long.

“Day-to-day temperatures in the 2010-11 Arctic winter did not reach lower values than in previous cold Arctic winters,” says Gloria Manney of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“The difference from previous winters is that temperatures were low enough to produce ozone-destroying forms of chlorine for a much longer time. This implies that if winter Arctic stratospheric temperatures drop just slightly in the future, for example as a result of climate change, then severe Arctic ozone loss may occur more frequently.”

The Arctic ‘hole’ was considerably smaller than those over the Antarctic, because the Arctic polar vortex – a persistent large-scale cyclone within which the ozone loss takes place – was about 40 percent smaller than those typical in the Antarctic.

But while the Arctic vortex is smaller and shorter-lived than its Antarctic counterpart, it’s more mobile, often moving over densely populated northern regions – raising health concerns.