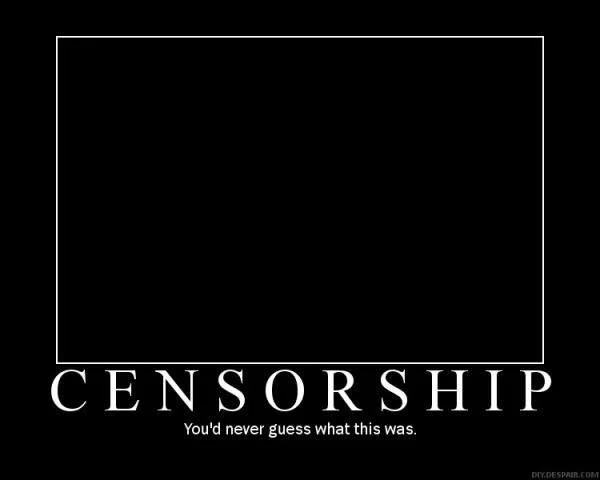

As WikiLeaks struggles to keep itself online, we are seeing an increase in corporate and government censorship aimed at controlling the flow of information.

Author and media studies professor Douglas Rushkoff says that this illustrates that the Internet is not and never has been democratically controlled.

“The stuff that goes on on the Internet does not go on because the authorities can’t stop it,” Douglas Rushkoff, author of Program or be Programmed: Ten Commands for a Digital Age and Life, Inc.: How Corporatism Conquered the World and How to Take it Back, said in a candid interview in The Raw Story. “It goes on because the authorities are choosing what to stop and what not to stop.”

You mean the authorities are picking and choosing what information they think they should block on some sort of a whim? That’s not really a surprise to people is it?

In The Raw Story Rushkoff said the authorities have the capability to halt cyber dissent because the Internet’s original design, as a top-down, authoritarian device with a system of centralized indexing.

More or less, all someone has to do to stop the website of a dissenter is to delete its address from the domain name system registry.

“This is not rocket science,” said Rushkoff, who also teaches media studies at the non-traditional school The New School University in Manhattan.

It may not be rocket science, but if Rushkoff’s simple explanation is true why didn’t the authorities simply stop WikiLeaks before they had a chance to expose all of the lies and corruption?

In an example to his explanation, Rushkoff refers to the Dutch teen arrested Thursday to helping to set up a denial of service attack on an “Operation Payback” chatroom: “They just took him off. He had his own server, and they just go, ‘Oh, nip this one!'” Rushkoff said.

That’s why he wrote in a CNN editorial that the actual threat to PayPal, Visa, MasterCard and Amazon were “vastly overstated” in most fawning corporate media outlets.

“The forces of bottom-up anarchy have reached a similar impasse, and the authorities of the Internet have once again demonstrated their ability to fend off any genuine peer-to-peer activity,” he explained. “This is a tightly controlled network, and you know, that’s why I think the Chinese do have it right in that they understand, ‘Oh, we can control this thing. We just censor the fu** out of it.”

“The general public didn’t realize that the only difference is now we can see that we’ve been censored.”

Rushkoff also said that until the recent WikiLeaks situation, no one has really talked about solid plans to create a truly democratic, peer-to-peer alternatives to the Internet’s centralized domain index since political activist Paul Garrin’s work in the 90’s.

For those not in the know, Garrin’s anti-trust lawsuit NAME.SPACE v. Network Solutions, Inc. led the way to lower domain registration costs by busting up the monopolistic domain name registration system into something more competitive and fair.

To Rushkoff this is proof that if someone doesn’t want to use the domain name servers that are “officially” in charge of the net, they can make their own network of domain name servers.

“If we want to have a true peer-to-peer network, we now understand what it might look like,” Rushkoff said. “If you want to have something real, we’ve got to build it from scratch.”

He makes some interesting points but if what Rushkoff says is true then makes you wonder why the government couldn’t simple point and click and have WikiLeaks offline before lunch.

Obviously Rushkoff is an expert in the concepts and cultural trends involving new media. His thoughts on building an alternative, open-source form of the Internet with less centralized registries is noteworthy.

However, his take on the WikiLeaks seems to oversimplify how easily the government can control cyber-rebellion when it suits them. When hackers are really motivated, or extremely pissed off they can be a tough group to deal with. They can create backdoors and overriding code that can be impossible to anticipate and difficult to crack.

Not every crafty and brilliant computer geek goes to work for Apple, Microsoft, and the government. Some of them hang out in the ether in case they are needed, apparently.

We may have to rely on these people to keep freedom of speech intact while we work on that alternative Internet model we need so dearly.