Thawing permafrost could release billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere by the end of this century, further accelerating global warming.

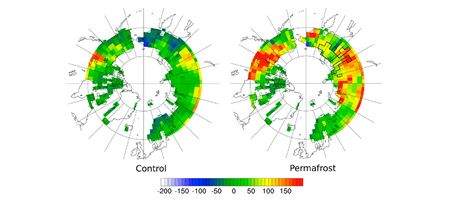

A new computer modeling study led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that soil in high-latitude regions could shift from being a carbon sink to a carbon dioxide source by the end of the century as the soil warms in response to climate change.

Their findings run counter to predictions included in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2007 fourth assessment report. This said found that climate change will spark a growth in high-latitude vegetation, pulling in more carbon from the atmosphere than thawing permafrost will release.

But, unlike earlier models, the new model includes detailed processes of how carbon accumulates in high-latitude soil over millennia, and how it’s released as permafrost thaws.

As a result, the new model found that the increase in carbon uptake by more vegetation will be overshadowed by a much larger amount of carbon released into the atmosphere.

“Previous models tended to dramatically underestimate the amount of soil carbon at high latitudes because they lacked the processes of how carbon builds up in soil,” says Berkeley Lab’s Charles Koven.

“Our model starts off with more carbon in the soil, so there is much more to lose with global warming.”

On the up side, the simulation found only a slight increase in methane release, contrary to previous predictions.

“People have this idea that permafrost thaw will release methane,” says Koven. “But whether carbon comes out as carbon dioxide or methane is dependent on hydrology and other fine-scale processes that models have a poor ability to resolve. It’s possible that warming at high latitudes leads to drying in many regions, and thus less methane emissions, and in fact this is what we found.”

Koven says his team is working to address large uncertainties that still remain in the model, such as the role of nitrogen feedbacks, which affect plant growth.

And he says that more research is needed to understand the processes that cause carbon to be released in permanently frozen, seasonally frozen, and thawed soil layers.