New tests of methane levels in the Gulf of Mexico have surprised scientists by revealing near-normal amounts. The team had expected levels to remain high for years.

According to researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara and Texas A&M University, more than 200,000 metric tons of dissolved methane have disappeared through the action of bacteria blooms.

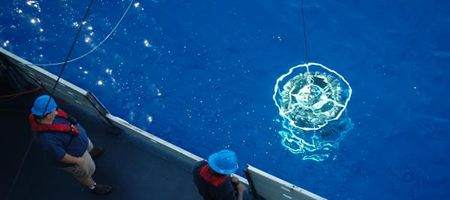

The team collected thousands of water samples at 207 locations covering an area of about 36,000 square miles, and examined dissolved methane concentrations, dissolved oxygen concentrations, methane oxidation rates, and microbial community structure.

In June, they found 100,000 times as much methane as usual. But, about 120 days after the initial spill, they could find only normal concentrations of methane and clear evidence of complete methane respiration.

“What we observed in June was a horizon of deep water laden with methane and other hydrocarbon gases,” said David Valentine of UCSB.

“When we returned in September and October and tracked these waters, we found the gases were gone. In their place were residual methane-eating bacteria, and a one million ton deficit in dissolved oxygen that we attribute to respiration of methane by these bacteria.”

The results show that the planet has its own ways of dealing with massive methane releases – and, indeed, many have occurred throught the planet’s history.

“The seafloor stores large quantities of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, which has been suspected to be released naturally, modulating global climate,” says John Kessler of Texas A&M.

“What the Deepwater Horizon incident has taught us is that releases of methane with similar characteristics will not have the capacity to influence climate.”