Princeton researchers say they’ve found a cheap and simple way to nearly triple the efficiency of organic solar cells.

Their nanostructured sandwich of metal and plastic collects and traps light, and can also be used in conventional inorganic solar collectors, such as standard silicon solar panels. And it’s ready for commercial use, they say.

Called a subwavelength plasmonic cavity, the sandwich is the foundation for a solar cell that absorbs as much as 96 percent of light, with 52 percent higher efficiency in converting light to electrical energy than a conventional solar cell.

It’s even more efficient with light that strikes the solar cell at large angles, for example on cloudy days or when the cell is not directly facing the sun, boosting efficiency by an extra 175 percent.

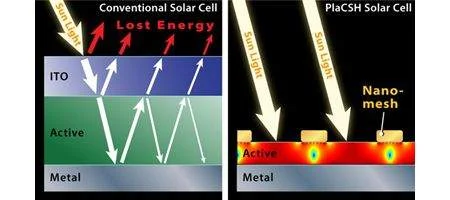

The top layer, known as the window layer, of the new solar cell uses an incredibly fine metal mesh: the metal is 30 nanometers thick, and each hole is 175 nanometers in diameter and 25 nanometers apart. This mesh replaces the conventional indium-tin-oxide (ITO) window layer.

The mesh window layer is placed very close to the bottom layer of the sandwich, the same metal film used in conventional solar cells; in between is a thin strip of semiconducting material of any type.

The solar cell’s features – the spacing of the mesh, the thickness of the sandwich, the diameter of the holes – are all smaller than the wavelength of the light being collected, so that the light can’t escape.

“It is like a black hole for light,” says professor Stephen Chou. “It traps it.”

The researchers say their PlaCSH solar cells can be manufactured cost-effectively in wallpaper-size sheets using ‘nanoimprint’: a low-cost technique Chou invented 16 years ago, which embosses nanostructures over a large area, like printing a newspaper.