AMD is pushing its Vision concept for all that it’s worth and has concluded that in an age when notebooks are all pervasive, the metrics used in the past fail to tell users what their machines can actually do.

The problem, of course, is that while AMD has what we consider is a reasonable point on consumers measuring price and performance, it certainly can’t go it alone.

And the problem too is that AMD doesn’t seem entirely clear what to replace the old metrics with. At its Lone Star facility in Austin, Texas, earlier this week, AMD showed a video it had made of customers at a local Best Buy store just a few days earlier. They were asked if they had heard of SysMark, BAPCO and the like and it’s obvious that although these were intelligent users who wanted the best out of the machines they were going to buy, those old metrics don’t mean anything to them at all.

Benchmarketing

David Schwarzbach and Hal Speed – great name that Hal – put some questions out to a band of about a dozen reviewers from the US and Europe, and it was pretty evident there aren’t any clear answers to the conundrum.

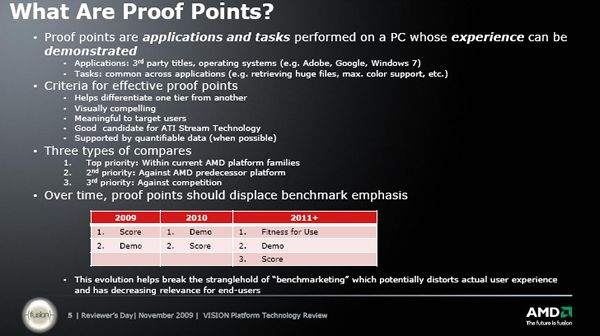

Schwarzbach said that AMD wanted to put across the idea that its Vision platforms convey, compared to benchmarks, which are fairly static. He said: “Fitness for use is at the heart of what we’re talking about. Our goal is to tailor a proof point to a usage model. Traditional standardized benchmarks have less and less meaning for most people.”

AMD has taken the view that although it was a product oriented company, it now needs to be a a platform company. He said that direct comparison to AMD’s competition – that is to say Intel – isn’t necessarily relevant. “This isn’t about AMD running from the fight at all.”

To demonstrate that, he said that AMD wanted to break the stranglehold of “benchmarketing” – that has decreasing relevance for end users, he said.

Washing Machines

Hal Speed said that standards for, example for washing machines in the EU show how all the different machines perform. And he said that while technically literate and sophisticated users can easily understand the traditional benchmarks, no magazine caters for mainstream consumers.

That led to a discussion that actually demonstrated the difficulty of providing information for regular buyers that would actually help them understand which machines are the best. And that raises several problems.

The first is that people who use notebook PCs have all sorts of applications they use – if you’re doing serious number crunching or graphics work, you are going to want to buy a machine that won’t keep you twiddling your thumbs while your boss waits for the results she or he wants.

The second is that PCs aren’t like washing machines at all. They’re sophisticated devices and their performance depends on operating systems, the amount of memory a PC has, the speed of a broadband connection, and numerous other variables make it hard to agree on a common metric anyway.

Subjective considerations such as how a machine looks, the brand, the size of the screen, and the touch of the keyboard all influence buying decisions when someone is standing in a Best Buy or a Staples and faced with an array of notebooks all with different specs. The sales person may or may not be savvy enough to guide a confused buyer through this maze.

Obviously AMD has its own internal benchmarks it uses, and a suggestion was made that these might be open sourced to the community. However, this suggestion wouldn’t necessarily go down well with publishers or magazines that had spent time and money building their own metrics.

Then, as this AMD slide below demonstrates, the “proof points” that Schwarzbach wants to emphasize over traditional benchmarks are themselves complicated.

AMD not only has to compare a machine in its Vision branding to other machines at a particular level, it has to compare those machines to PCs that used its own predecessor CPUs and to competing Intel-based machines.

It’s pretty clear from the conversation that some of these problems are well nigh insuperable – AMD and Intel constantly compare their CPUs to each other, and differentiation is an important element, with different SKUs (stock keeping units), all adding to the profitabilty or otherwise of a CPU. While that competitive situation remains – and of course there’s competition between vendors that make notebooks as well – it’s unlikely that the industry will come to any concensus about benchmarks for the mass market.