A Columbia Engineering School team says it’s made a major step in improving forecasts of extreme weather events in the US.

Atmospheric processes, particularly rainfall, are influenced by moisture and heat fluctuations from the land surface to the atmosphere. But while current theory has suggested that soil moisture increases precipitation, there’s been little observational evidence of this.

Now, though, the Columbia Engineering Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and Rutgers University have used data from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) to show that evaporation from the land can affect summertime rainfall east of the Mississippi and in the southern US and Mexico. However, it only modifies the frequency of summertime rainfall, not its quantity.

It has no influence on rainfall over the Western US.

“This is a major shift in our understanding of the coupling between the land surface and the atmosphere, and fundamental for our understanding of the prolongation of hydrological extremes like floods and droughts,” says Pierre Gentine, assistant professor of applied mathematics.

The difference is due to the humidity present in the atmosphere. The atmosphere over the western regions is so dry that however much water evaporates from the surface, it won’t trigger any rain – instead, it will instantaneously dissipate into the atmosphere.

However, the atmosphere over the eastern regions is sufficiently wet so that the added moisture from the surface evaporation will make it rain.

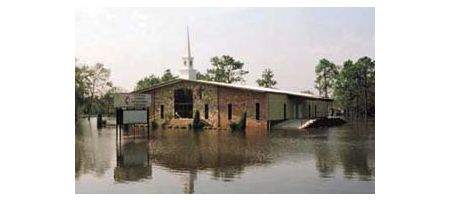

“If it starts getting really wet in the east, then the surface will trigger more rain so it becomes even moister, and this sets up a vicious cycle for floods and droughts,” says Gentine.

“Nature — ie the land surface and the vegetation — cannot control the rainfall process in the west but it can in the east and in the south. This is really important in our understanding of the persistence of floods and droughts.”

As a result, once a flood or a drought begins, it’s most likely to persist in the eastern and southern US. But in the West, whether the soil is dry or wet doesn’t change subsequent rainfalls, meaning that floods or droughts will pass more quickly.