Globular clusters are approximate spherical collections of old stars, with around 150 of them scattered around our Milky Way galaxy.

NASA’s Hubble is one of the most appropriate telescopes for studying these stellar phenomenon, as its extremely high resolution allows astronomers to accurately observe individual stars, even in the crowded core.

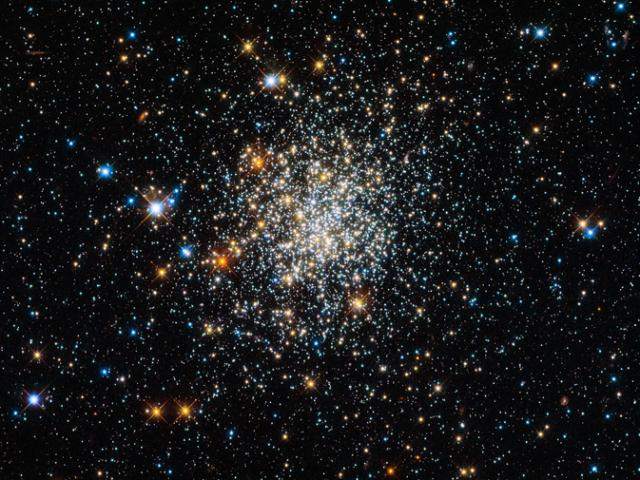

The clusters all appear very similar, and in Hubble’s images it can be quite hard to tell them apart, as they appear much like NGC 411, pictured above.

Nevertheless, appearances can be deceptive, as NGC 411 is in fact not a globular cluster, and its stars are not old. To be sure, it isn’t even in the Milky Way. Indeed, NGC 411 is classified as an open cluster located in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a small sister galaxy near our own.

Less tightly bound than a globular cluster, the stars in open clusters tend to drift apart over time as they age, whereas globulars have survived for well over 10 billion years of galactic history.

NGC 411 is a relative youngster, not much more than a tenth of this age. Far from being a relic of the early years of the universe, the stars in NGC 411 are in fact a fraction of the age of the sun.

The stars in NGC 411 are all roughly the same age, having formed at one time from one cloud of gas. But they are not all the same size.

As you can see in the image above, Hubble’s image shows a wide range of colors and brightness in the cluster’s stars; these relay numerous facts about the stars, including their mass, temperature and evolutionary phase. Blue stars, for example, have higher surface temperatures than red ones.

It should be noted that the image above is actually a composite produced from ultraviolet, visible and infrared observations made by Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3. This filter set lets the telescope “see” colors slightly further beyond red and the violet ends of the spectrum.