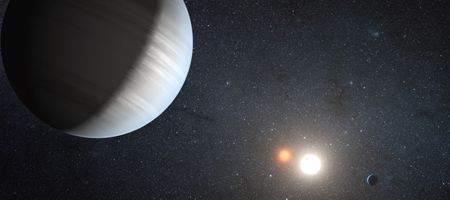

NASA’s Kepler mission has for the first time discovered multiple planets orbiting a pair of stars, showing it’s possible for more than one planet to be formed and survive in such a chaotic environment.

The system, known as a circumbinary planetary system, is 4,900 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus. It consists of two orbiting stars, one similar to the sun in size, but only 84 percent as bright, and the other only one-third the size of the sun and less than one percent as bright.

“In contrast to a single planet orbiting a single star, the planet in a circumbinary system must transit a ‘moving target.’ As a consequence, time intervals between the transits and their durations can vary substantially, sometimes short, other times long,” says Jerome Orosz, associate professor of astronomy at San Diego State University. “The intervals were the telltale sign these planets are in circumbinary orbits.”

The inner planet, Kepler-47b, orbits the pair of stars in less than 50 days and is thought to be very hot, with the destruction of methane in its super-heated atmosphere leading to a thick blanket of haze. At three times the radius of Earth, it’s the smallest known transiting circumbinary planet.

The outer planet, Kepler-47c, orbits its host pair every 303 days, placing it in the habitable zone, where liquid water might exist. It’s not hospitable for life, though, but a gaseous giant slightly larger than Neptune, where an atmosphere of thick bright water-vapor clouds might exist.

“The presence of a full-fledged circumbinary planetary system orbiting Kepler-47 is an amazing discovery,” says Greg Laughlin, professor of Astrophysics and Planetary Science at the University of California in Santa Cruz.

“These planets are very difficult to form using the currently accepted paradigm, and I believe that theorists, myself included, will be going back to the drawing board to try to improve our understanding of how planets are assembled in dusty circumbinary disks.”