Yesterday, an invader from another planet fired off a laser 30 times, in what we have to hope won’t be seen as an act of aggression by any overlooked Martian inhabitants.

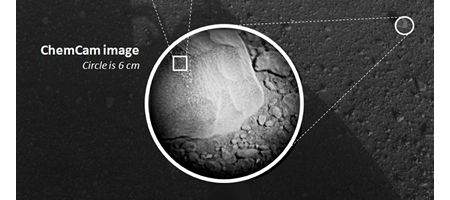

The Curiosity rover was using the laser to examine a fist-sized rock, dubbed Coronation, with its Chemistry and Camera instrument, or ChemCam.

Over a ten-second period, it zapped the rock with 30 laser pulses, each one delivering more than a million watts of power for about five billionths of a second.

The aim was mainly target practice, to calibrate the instrument, although the scientists also hope to learn more about the composition of the Martian surface. The laser’s energy excites atoms in the rock into an ionized, glowing plasma, and ChemCam analyzes this glow with its three spectrometers to identify the elements contained within.

The spectrometers record intensity at 6,144 different wavelengths of ultraviolet, visible and infrared light.

“We got a great spectrum of Coronation – lots of signal,” says ChemCam principal investigator Roger Wiens of Los Alamos National Laboratory. “Our team is both thrilled and working hard, looking at the results. After eight years building the instrument, it’s payoff time!”

ChemCam recorded spectra from the laser-induced spark at each of the 30 pulses, and researchers will now check to see whether the composition changed as the pulses progressed.

If it did change, that could indicate that the instrument has penetrated dust or other surface material to reveal a different composition beneath the surface. Ultimately, the hope is that the instrument will be able to reveal whether rocks on Mars have ever been altered by water and contain chemicals necessary for life..

The same technique – called laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy – has been used on Earth to determine the composition of targets in other extreme environments, such as inside nuclear reactors and on the sea floor. It’s also been tested in environmental monitoring and cancer detection.

Yesterday’s investigation of Coronation, though, is the first use of the technique in interplanetary exploration, and the team’s very pleased with the results.

“It’s surprising that the data are even better than we ever had during tests on Earth, in signal-to-noise ratio,” says ChemCam deputy project scientist Sylvestre Maurice of the Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planetologie in France.

“It’s so rich, we can expect great science from investigating what might be thousands of targets with ChemCam in the next two years.”