An analysis of river networks on Titan indicates that some recent phenomenon may have altered the face of Saturn’s largest moon.

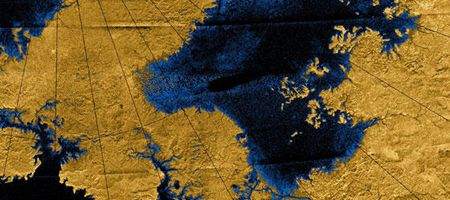

In 2004, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft sent back the first detailed images of the surface, revealing an icy terrain carved out over millions of years by rivers of liquid methane.

Now, though, researchers at MIT and the University of Tennessee at Knoxville have analyzed images of Titan’s river networks and discovered that, in some regions, rivers have created surprisingly little erosion.

There are two possible explanations, they say: either erosion on Titan is extremely slow, or some other recent phenomenon may have wiped out older riverbeds and landforms.

“It’s a surface that should have eroded much more than what we’re seeing, if the river networks have been active for a long time,” says geologist Taylor Perron of MIT.

“It raises some very interesting questions about what has been happening on Titan in the last billion years.”

Titan’s much smoother than most moons in our solar system, all of which date back about four billion years. From the number of craters, though, one might think it much younger, between 100 million and one billion years old.

One explanation may be that, as on Earth, tectonic upheaval, icy lava eruptions, erosion and sedimentation by rivers may be at work.

And comparing the images of Titan with recently renewed landscapes on Earth – including volcanic terrain on the island of Kauai and recently glaciated landscapes in North America – shows strong similarities.

The river networks in those locations look a lot like those on Titan, suggesting that geologic processes may have reshaped the moon’s icy surface comparatively recently.

“It’s a weirdly Earth-like place, even with this exotic combination of materials and temperatures,” Perron says. “And so you can still say something definitive about the erosion. It’s the same physics.”