Scientists at the University of South Florida (USF) have created an anomaly that could allow graphene to eventually replace silicon as the primary material in electronic devices.

Indeed, previous attempts at creating anomalies proved inconsistent and produced samples in which only the edges of thin strips of graphene or graphene nanoribbons contained a useful defect structure.

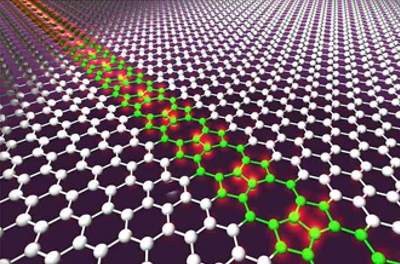

However, the USF team developed a method of producing a well-defined, extended defect several atoms across which contains octagonal and pentagonal carbon rings embedded in a perfect graphene sheet.

According to PhysOrg, the defect functions as a quasi, one-dimensional metallic wire that conducts electric current and can be used as metallic interconnects or elements of device structures of all-carbon, atomic-scale electronics.

To create the anomaly, the team used the self-organizing properties of a single-crystal nickel substrate, along with a metallic surface as a scaffold to synthesize two graphene half-sheets.

When the two halves merged, they naturally formed an extended line defect with a well-defined, periodic atomic structure and metallic properties within the narrow strip along the defect.

“This tiny wire could have a big impact on the future of computer chips and the myriad of devices that use them. In the late 20th century, computer engineers described a phenomenon called Moore’s Law, which holds that the number of transistors that can be affordably built into a computer processor doubles roughly every two years,” explained PhysOrg.

“This law has proven correct and society has been reaping the benefits as computers become faster, smaller and cheaper. In recent years, however, some physicists and engineers have come to believe that without new breakthroughs in new materials, we may soon reach the end of Moore’s Law. [But] Metallic wires in graphene may help to sustain the rate of microprocessor technology predicted by Moore’s Law well into the future.”