Antibiotic-resistant bacteria are nothing new – they’ve been around for at least 30,000 years, say scientists at McMaster University.

“Antibiotic resistance is seen as a current problem and the fact that antibiotics are becoming less effective because of resistance spreading in hospitals is a known fact,” says Gerry Wright, scientific director of the Michael G DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

“The big question is where does all of this resistance come from?”

His team studied bacterial DNA extracted from soil frozen in 30,000-year-old permafrost from the Yukon Territories, isolating small stretches of ancient DNA.

And they discovered that antibiotic resistant genes existed alongside genes that encoded DNA for ancient life, such as mammoths, horse and bison as well as plants.

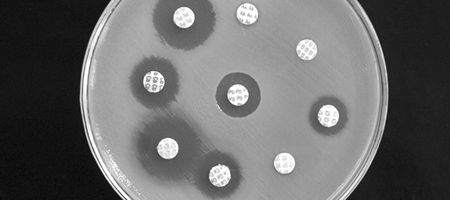

The researchers focused on a specific area of antibiotic resistance to the drug vancomycin, a significant clinical problem that emerged in 1980s and that’s still associated with outbreaks of hospital-acquired infections worldwide.

They found that these genes were present in the permafrost at depths consistent with the age of the other DNAs, such as the mammoth. They then recreated the gene product in the lab, purified its protein and showed that it had the same activity and structure then as it does now.

This is only the second time an ancient protein has been ‘revived’ in a laboratory setting.

According to Wright, the breakthrough will have an important impact on the understanding of antibiotic resistance.

“Antibiotics are part of the natural ecology of the planet, so when we think that we have developed some drug that won’t be susceptible to resistance or some new thing to use in medicine, we are completely kidding ourselves,” he says.

“These things are part of our natural world and therefore we need to be incredibly careful in how we use them. Microorganisms have figured out a way of how to get around them well before we even figured out how to use them.”