Colorful church windows, beads on a necklace and many of our favorite plastics share something in common — they all belong to a state of matter known as glasses. School children learn the difference between liquids and gases, but centuries of scholarship have failed to produce consensus about how to categorize glass.

Now, combining theory and numerical simulations, researchers have resolved an enduring question in the theory of glasses by showing that their energy landscapes are far rougher than previously believed. The findings appear April 24 in the journal Nature Communications.

“There have been beautiful mathematical models, but with sometimes tenuous connection to real, structural glasses. Now we have a model that’s much closer to real glasses,” said Patrick Charbonneau, one of the co-authors and assistant professor of chemistry and physics at Duke University.

The new model, which shows that molecules in glassy materials settle into a fractal hierarchy of states, unites mathematics, theory and several formerly disparate properties of glasses.

One thing that sets glasses apart from other phase transitions is a lack of order among their constituent molecules. Their cooled particles become increasingly sluggish until, caged in by their neighbors, the molecules cease to move — but in no predictable arrangement. One way for researchers to visualize this is with an energy landscape, a map of all the possible configurations of the molecules in a system.

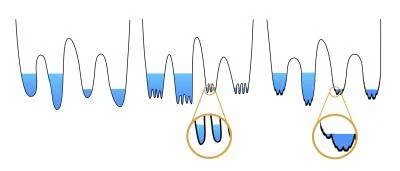

Charbonneau said a simple energy landscape of glasses can be imagined as a series of ponds or wells. When the water is high (the temperature is warmer), the particles within float around as they please, crossing from pond to pond without problem. But as you begin to lower the water level (by lowering the temperature or increasing the density), the particles become trapped in one of the small ponds. Eventually, as the pond empties, the molecules become jammed into disordered and rigid configurations.

“Jamming is what happens when you take sand and squeeze it,” Charbonneau said. “First it’s easy to squeeze, and then after a while it gets very hard, and eventually it becomes impossible.”

Like the patterns of a lakebed revealed by drought, researchers have long wondered exactly what “shape” lies at the bottom of glass energy landscapes, where molecules jam. Previous theories have predicted the bottom of the basins might be smooth or a bit rough.

“At the bottom of these lakes or wells, what you find is variation in which particles have a force contact or bond,” Charbonneau said. “So even though you start from a single configuration, as you go to the bottom or compress them, you get different realizations of which pairs of particles are actually in contact.”

Charbonneau and his co-authors based in Paris and Rome showed, using computer simulations and numeric computations, that the glass molecules jam based on a fractal regime of wells within wells.

The new description makes sense of several behaviors seen in glasses, like the property known as avalanching, which describes a random rearrangement of molecules that leads to crystallization.

“There are a lot of properties of glasses that are not understood, and this finding has the potential to bring together a wide range of those problems into one coherent picture,” said Charbonneau.

Understanding the structure of glasses is more than an intellectual exercise — materials scientists stand to advance from the knowledge, which could lead to better control of the aging of glasses.