Air pollution from Asia has been rising for several decades but Hawaii had seemed to escape the ozone pollution that drifts east with the springtime winds. Now a team of researchers has found that shifts in atmospheric circulation explain the trends in Hawaiian ozone pollution.

The researchers found that since the mid-1990s, these shifts in atmospheric circulation have caused Asian ozone pollution reaching Hawaii to be relatively low in spring but rise significantly in autumn. The study, led by Meiyun Lin, an associate research scholar in the Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (NOAA) at Princeton University and a scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, was published in Nature Geoscience.

“The findings indicate that decade-long variability in climate must be taken into account when attributing U.S. surface ozone trends to rising Asian emissions,” Lin said. She conducted the research with Larry Horowitz and Songmiao Fan of GFDL, Samuel Oltmans of the University of Colorado and the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder; and Arlene Fiore of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University.

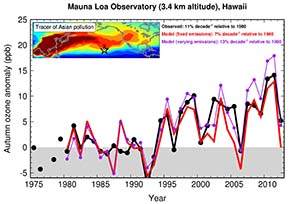

Although protective at high altitudes, ozone near the Earth’s surface is a greenhouse gas and a health-damaging air pollutant. The longest record of ozone measurements in the U.S. dates back to 1974 in Hawaii. Over the past few decades, emissions of ozone precursors in Asia has tripled, yet the 40-year Hawaiian record revealed little change in ozone levels during spring, but a surprising rise in autumn.

Through their research, Lin and her colleagues solved the puzzle. “We found that changing wind patterns ‘hide’ the increase in Asian pollution reaching Hawaii in the spring, but amplify the change in the autumn,” Lin said.

Using chemistry-climate models and observations, Lin and her colleagues uncovered the different mechanisms driving spring versus autumn changes in atmospheric circulation patterns. The findings indicate that the flow of ozone-rich air from Eurasia towards Hawaii during spring weakened in the 2000s as a result of La-Niña-like decadal cooling in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. The stronger transport of Asian pollution to Hawaii during autumn since the mid-1990s corresponds to a positive pattern of atmospheric circulation variability known as the Pacific-North American pattern.

“This study not only solves the mystery of Hawaiian ozone changes since 1974, but it also has broad implications for interpreting trends in surface ozone levels globally,” Lin said. “Characterizing shifts in atmospheric circulation is of paramount importance for understanding the response of surface ozone levels to a changing climate and evolving global emissions of ozone precursors,” she said.