A trick used by fish to overcome a basic law of physics could lead to improvements in the efficiency of LED lights.

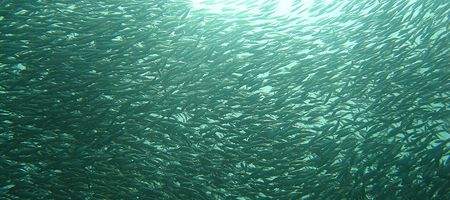

Silvery fish such as sardines and herring don’t polarize light in the way that most relective surfaces do, possibly to help them avoid predators.

Previously, it was thought that the fish’s skin – which contains multilayer arrangements of reflective guanine crystals – would fully polarize light, and therefore become less reflective.

But University of Bristol researchers have found that the skin of these fish contain not one but two types of guanine crystal – each with different optical properties. By mixing these two types, the fish’s skin doesn’t polarize the reflected light and maintains its high reflectivity.

“We believe these species of fish have evolved this particular multilayer structure to help conceal them from predators, such as dolphin and tuna,” says Dr Nicholas Roberts.

“These fish have found a way to maximize their reflectivity over all angles they are viewed from. This helps the fish best match the light environment of the open ocean, making them less likely to be seen.”

As a result of this ability, says the team, the skin of silvery fish could hold the key to better optical devices.

“Many modern day optical devices such as LED lights and low loss optical fibres use these non-polarizing types of reflectors to improve efficiency. However, these man-made reflectors currently require the use of materials with specific optical properties that are not always ideal,” says PhD stident Tom Jordan.

“The mechanism that has evolved in fish overcomes this current design limitation and provides a new way to manufacture these non-polarizing reflectors.”