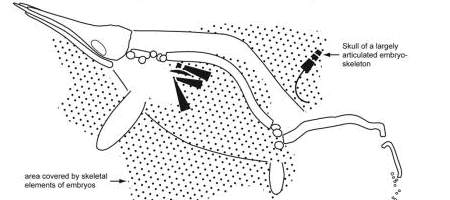

For years, scientists have puzzled over the skeleton of a pregnant ichthyosaur which, while in good condition itself, was surrounded by the scattered bones of its unborn offspring.

It’s long been believed that the explanation must be that the gases of putrefaction had caused the mother’s carcass to explode, ejecting the embryos.

However, new research from a group of European scientists appears to have laid this rather delightful theory to rest.

Their method, based on the observation that people are much the same size as icthyosaurs, involved examining the decomposition of 100 human corpses.

In order to gauge the pressure of the particular gases that can actually develop inside a putrefying ichthyosaur, the researchers inserted a manometer into the abdomen of one hundred corpses – and found that the putrefaction gas pressures measured only 0.035 bar.

To burst an ichthyosaur resting under 50 to 150 meters of water, they say, you’d need five to 15 bar to generate an explosion.

Zurich paleontologist Christian Klug concludes: “Large vertebrates that decompose cannot act as natural explosive charges. Our results can be extended to lung-breathing vertebrates in general.”

So what, then, did happen 182 million years ago? The team has worked out a possible scenario.

Normally, bodies would have sunk to the seabed immediately after death, breaking down completely in deeper waters. At depths of less than 50 meters and a temperature of over four degrees Celsius, though, putrefaction gases would often have brought them back to the surface.

Here, exposed to the waves and scavengers, they’d have decomposed within a few weeks. Bones would have been scattered over a wide area on the seabed as they sank, says the team.