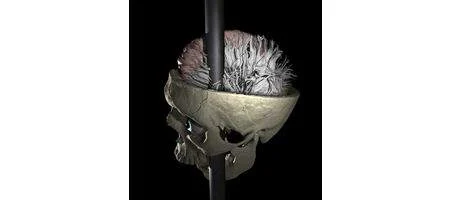

Neurologists have modeled the damage caused to a man’s brain when a three-foot metal bar was driven through his head – over 160 years after the accident happened.

In 1848, railway supervisor Phineas Gage became the most famous case in the history of neuroscience when a chance explosion drove the rod through his left cheek and out of the top of his head.

Much of his left frontal lobe was destroyed and, famously, his personality was changed, with Gage becoming erratic and bad-tempered.

Until now, it’s not been known exactly where and how badly Gage’s brain was damaged. But UCLA researchers have now used brain-imaging data to look at the damage to the white matter ‘pathways’ that connect various regions of the brain.

While around four percent of the cerebral cortex was intersected by the rod’s passage, they say, more than 10 percent of Gage’s total white matter was damaged.

“What we found was a significant loss of white matter connecting the left frontal regions and the rest of the brain,” says UCLA assistant professor of neurology Jack Van Horn.

“We suggest that the disruption of the brain’s ‘network’ considerably compromised it. This may have had an even greater impact on Mr Gage than the damage to the cortex alone in terms of his purported personality change.”

Since Gage’s skull, which is on display in the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard Medical School, is now fragile and unlikely to again be subjected to medical imaging, the researchers had to track down the last known imaging data, from 2001, which had been lost for some 10 years.

The team was able to recover the computed tomographic data files and managed to reconstruct the scans. Next, they utilized advanced computational methods to model and determine the exact trajectory of the tamping iron that shot through his skull. Finally, they used modern-day brain images of males that matched Gage’s age and handedness, then used software to position a composite of these 110 images into Gage’s virtual skull.

“Our work illustrates that while cortical damage was restricted to the left frontal lobe, the passage of the tamping iron resulted in the widespread interruption of white matter connectivity throughout his brain, so it likely was a major contributor to the behavioral changes he experienced,” says Van Horn.

“Connections were lost between the left frontal, left temporal and right frontal cortices and the left limbic structures of the brain, which likely had considerable impact on his executive as well as his emotional functions.”

Gage eventually was able to travel and worked as a stagecoach driver for several years in South America. He died in San Francisco, 12 years after the accident.