Berkeley Lab scientists are soon to move into clinical trials of a pill that can decontaminate people after exposure to radiation.

Currently, there’s only one chemical agent available that can do this, a compound known as DTPA. It’s been around since the Cold War, and must be administered intravenously – and, even then, it only removes some of the deadly actinides that pose the greatest health threat.

The Berkeley Lab pill, though, gets rid of a far greater range of the actinides likely to be part of the radiation exposure from a nuclear plant or weapon, including plutonium, americium, curium, uranium and neptunium.

And depending on the level of radiation exposure and how soon treatment can start, just one of these pills can eliminate around 90 percent of the actinide contaminants within 24 hours. A pill taken daily for two weeks should get rid of virtually all of them.

“With the expanding use of nuclear power and unfortunate possibility of nuclear weapon use, there is an urgent need to develop and implement an improved therapy for actinide contamination of a large population,” says Berkeley Lab’s Rebecca Abergel.

“We are now in the process of demonstrating that our actinide-specific decontaminating agents are ready for clinical development.”

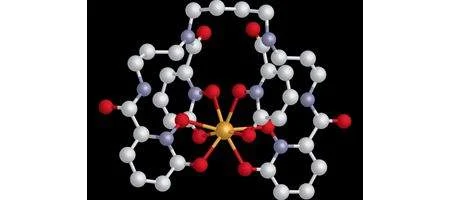

The pill is based on sequestering agents that can encapsulate actinides into tightly bound cage-like chemical complexes for transport out of the body. The team’s concentrated on plutonium and natural chelators, the crablike molecules that specifically bind with iron and other metal ions.

“Since the biochemical properties of plutonium and iron are similar, we modeled our sequestering agents after the chelating unit found in siderophores [small molecules secreted by bacteria to extract and solubilize iron],” says Ken Raymond, a professor of chemistry at UC Berkeley.

“This biomimetic approach enabled us to design multidentate hydroxypyridonate ligands that are unrivaled in terms of actinide-affinity, selectivity and efficiency.”

The team’s now got its two candidate ligands through the initial phases of pre-clinical development, and has carried out extensive studies in animal models and human cell lines that established the two HOPO candidates as being highly effective and non-toxic.

They’re now started working with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to determine what further data is needed to move into clinical trials. Typically, at this stage of development, a private pharmaceutical company would step in – but Abergel says it’s difficult to attract private investors for a drug that will hopefully never be needed.

“As we move further along with the FDA process it should be easier to convince private pharmaceutical companies to get involved,” she says.