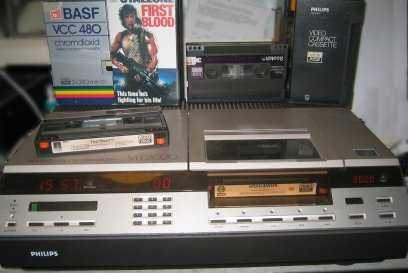

During the early days of the home video revolution, VCRs were really expensive and so were movies on VHS and Betamax.

Still, I thought it would be the coolest thing in the world to own a VCR, along with tons of movies I could watch at any time. At first the machines were bulky, and the tape was ¾ inch, then the equipment became more compact, and the prices also came down to earth.

Anyone’s who’s a fan of classic horror may remember the company Wizard Video, who put out The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Zombie, and I Spit On Your Grave.

Charles Band, who started Wizard, also launched Media Home Video, another big independent company that released Halloween on video, and tons of crazy cult movies.

The major studios always believed technology would ruin the business, and were slow to react to the home video boom, but people like Band were able to buy movie rights very cheaply, and launch their own companies dubbing movies from VCR to VCR, just like the rest of us when we copy movies.

At the dawn of the VCR boom, Andre Blay started a video company called Magnetic Video, and bought the home video rights for movies like Alien and Planet of the Apes for peanuts because there were no rentals at the time, and movies were still expensive to buy. Even though Band could have gone to the majors as well, because they were giving away the rights for peanuts, he went after the popular independent films of the time that played the midnight circuit.

Band went to a number of independent film companies, buying up the rights to their most successful and popular titles. At first they viewed Band with skepticism. “It was almost like a chuckle,” he says. “‘Here comes this lunatic who’s gonna give us money to license these video rights’ for a movie they exploited years ago.” Ultimately, the companies figured why not try it?

“You can also look at it differently,” Band continues. “This could have been a technology that failed, and I could have been the dummy that gave thousands of dollars for rights that really had no history or value at the time. I was the first one knockin’ at the door, and they just saw some guy walking in wanting some obscure body of rights. That it went my way was great.”

Band would often pay $5,000 for world-wide rights on a film for a five year period. Band set up shop in the back room of his offices in Santa Monica, with a three quarter inch machine playing the master copy of a film, and ten slave machines doing the duping.

Beta was the only format around at the time, but it wasn’t long before VHS became the preferred format, making Beta obsolete (this was particularly humiliating to Sony, who stubbornly refused to work with VHS technology until Beta got obliterated). Early video stores carried films in both formats, and now Band had to get VHS machines to keep up.

“This was all within months,” Band says. At first he would get an order for ten pieces, but it wasn’t long before he got an order for a hundred and fifty pieces. He figured, “Well, we better go out and find a cheaper way to buy tape.” Then one day Band came to work and received an order for six hundred pieces. “I didn’t even have enough slaves to replicate that many in real time,” he says. “The company started almost like a hobby to, ‘How do we buy a thousand blank Betas and VHS cassettes to replicate this stuff? How do we get twenty more machines?’ It was exploding, and Media evolved very quickly into a real business.”

Band recalled in Filmmaking on the Fringe that two years after he left Media, his partners sold the company for about $20 million. Today he says, “If I could take all my knowledge back in the day, I would have done things differently. I was in my early twenties, I had no real business training. But you’re more prepared as you get older in experience with handling rare opportunities. If they come early on, you usually mess ’em up or fumble ’em a bit.”

Now the home video market was thriving, and stores were popping up everywhere. “There was a point in ’82 or ’83, I don’t know how many tens of thousands of video stores were out there,” Band says. “And we’re not talking about a chain, they were Ma and Pa operations.” (The very first video store, Video Station, opened on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles in 1977, and it was reportedly the first store that rented videos, at $10 a day).

The majors were also catching on by this point. Although you can make a good case that the majors still wait for someone else to pioneer a new technology, again usually the porno people, Band says, “Today the majors are absolutely on top of new technology. They’ve got thousands of people looking under every rock. I don’t think they’ll ever be a time again when the majors are asleep at the wheel. When it comes to technology, everyone knows this is what fuels the business and puts new life into libraries.”