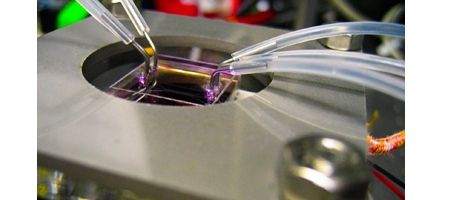

MIT’s developed a way to grow an entire electronic device in a flask of liquid. The team demonstrated the technique, called hydrothermal synthesis, by producing a working LED array made of zinc oxide nanowires in a microfluidic channel.

They didn’t need expensive semiconductor manufacturing processes and facilities, just a syringe to push solution through a capillary tube one-tenth of a millimeter wide.

“For nanostructures, there’s a coupling between the geometry and the electrical and optical properties,” says researcher Brian Chow.

“Being able to rationally tune the geometry is very powerful because you can, in turn, tune the functional properties.”

The system can control the aspect ratio of the nanowires to produce anything from flat plates to long, thin wires. While there are other ways to do this, says Chow, it generally requires much high temperatures or the use of inorganic solvents.

The MIT method depends on the electrostatic properties of the zinc oxide material as it grows from a solution. The ions of different compounds, when added to the solution, attach themselves electrostatically only to certain parts of the wire — just to the sides, or just to the ends — inhibiting its growth in those directions.

Applications based on the zinc oxide material that MIT used include the production of batteries, sensors and optical devices. And the processing method has the potential for large-scale manufacturing, they say.

But the method could work with other materials, too – perhaps including titanium dioxide, which is being investigated for devices such as solar cells. Because the low-temperature assembly conditions allow the material to be grown on plastic surfaces, he says, it could enable the development of flexible display panels, for example.