A team from Vanderbilt University says it’s found a quick and easy way of producing low cost nanodevices.

It works with porous nanomaterials, whose tiny holes give them unique optical, electrical, chemical and mechanical properties. They have a wide range of applications including chemical and biological sensors, solar cells and battery electrodes. There are nanoporous forms of gold, silicon, alumina, and titanium oxide, among others.

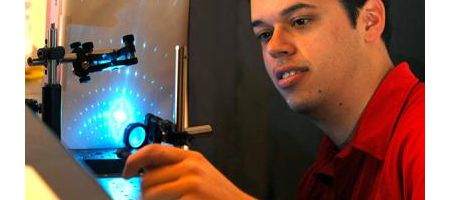

The only problem is that, up to now, the necessary processing has been complex and expensive. But, says electrical engineering professor Sharon Weiss, the answer is to simply stamp them out.

“It’s amazing how easy it is. We made our first imprint using a regular tabletop vise,” she says. “And the resolution is surprisingly good.”

Traditionally, device manufacture requires a special clean room and involves painting the surface with a material called a resist, exposing it to ultraviolet light or scanning the surface with an electron beam to create the desired pattern and then applying a series of chemical treatments to either engrave the surface or lay down new material. The more complicated the pattern, the longer it takes to make.

But Weiss had the idea of creating pre-mastered stamps using the complex process, and then using these to create the devices. Her direct imprinting of porous substrates (DIPS) approach can create a device in less than a minute, regardless of its complexity, and her group has used master stamps more than 20 times without any signs of deterioration.

The smallest pattern that Weiss and her colleagues have made to date has features of only a few tens of nanometers. They have also succeeded in imprinting the smallest pattern yet reported in nanoporous gold, one with 70-nanometer features.

The group has used the new technique to make nano-patterned chemical sensors that are ten times more sensitive than a commercial chemical sensor.

The university has applied for a patent on the DIPS method.