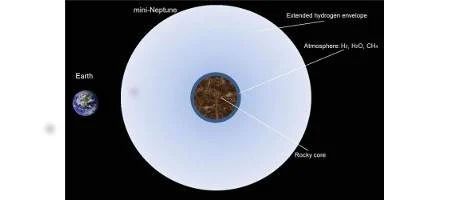

So-called super-Earths – rocky exoplanets much larger than our own – may actually be more like mini-Neptunes.

According to scientists at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, these planets may actually be surrounded by extended hydrogen-rich envelopes and that they are unlikely to ever become Earth-like.

Super-Earths follow a different evolutionary track to the planets found in our solar system, and there’s been some debate over whether they can evolve to become rocky bodies like the terrestrial planet’ Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars.

To try tofind out, Dr Helmut Lammer and his team looked at the impact of radiation on the upper atmospheres of super-Earths orbiting the stars Kepler-11, Gliese 1214 and 55 Cancri.

These planets are all several times more massive and slightly larger than Earth, and orbit very close to their stars. The way in which the mass of planets scales with their sizes suggests that they have solid cores surrounded by hydrogen or hydrogen-rich atmospheres, probably captured from the clouds of gas and dust from which they formed.

The new model suggests that the short wavelength extreme ultraviolet lightof the host stars heats up the gaseous envelopes of these worlds, so that they expand up to several times the radius of each planet and gas escapes from them fairly quickly. Nonetheless, most of the atmosphere remains in place over the whole lifetime of the stars they orbit.

“Our results indicate that, although material in the atmosphere of these planets escapes at a high rate, unlike lower mass Earth-like planets many of these super-Earths may not get rid of their nebula-captured hydrogen-rich atmospheres,” says Lammer.

Rather than becoming more like Earth, the super-Earths may end up more closely resembling gas giants like Neptune. If so, then super-Earths further out from their stars in the ‘habitable zone’, where the temperature would allow liquid water to exist, would hold on to their atmospheres even more effectively – making them much less likely to be habitable.