Scientists at the University of British Columbia and the Smithsonian Institution have discovered a new sensory organ in rorqual whales that appears to tell it when it’s worth taking a big gulp.

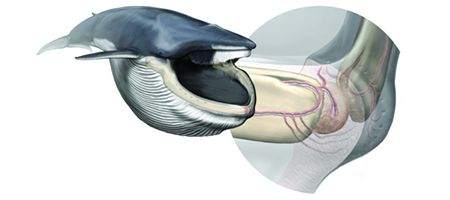

Rorquals are a subgroup of baleen whales with a special, accordion-like blubber layer that goes from the snout to the navel. The blubber expands to allow the whales to engulf large quantities of water and filter out krill and fish.

Samples were collected from recently-killed whale carcasses derived from Icelandic commercial whaling operations, and examined using X-ray computed tomography.

And the scientists discovered a grapefruit-sized sensory organ at the tip of the whale’s chin, lodged in the ligamentous tissue that connects its two jaws and supplied by neurovascular tissue.

“We think this sensory organ sends information to the brain in order to coordinate the complex mechanism of lunge-feeding, which involves rotating the jaws, inverting the tongue and expanding the throat pleats and blubber layer,” says Nick Pyenson, a paleobiologist at the Smithsonian Institution. “It probably helps rorquals feel prey density when initiating a lunge.”

One type of rorqual, the fin whale, can engulf as much as 80 cubic metres of water and prey – often a greater volume than that of the whale itself – in each gulp, in less than six seconds. Each gulp captures 10 kilograms of krill.

“In terms of evolution, the innovation of this sensory organ has a fundamental role in one of the most extreme feeding methods of aquatic creatures,” says University of British Columbia zoology professor Bob Shadwick.

“Because the physical features required to carry out lunge-feeding evolved before the extremely large body sizes observed in today’s rorquals, it’s likely that this sensory organ – and its role in coordinating successful lunging – is responsible for rorquals claiming the largest-animals-on-earth status.”