While Greenland’s glaciers are moving ever-faster twowards the sea, they’re not accelerating as much as believed, indicating that future sea level rises could be a lot less than current worst-case scenarios.

Previous studies have lacked precise data for how major ice regions, primarily in Greenland and Antarctica, were behaving in the face of climate change.

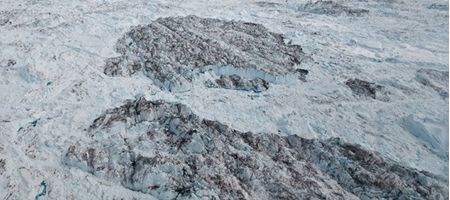

But, in the new study, a team from Washington University and Ohio State University created a decadelong record of changes in Greenland outlet glaciers by producing velocity maps based on satellite data.

And, they found, the outlet glaciers weren’t moving as fast had been speculated.

“In some sense, this raises as many questions as it answers. It shows there’s a lot of variability,” says UW glaciologist Ian Joughin.

Unfortunately, the data gives no reason to think that the glaciers will stop gaining speed during the rest of the century, and so by 2100 they could stillcontribute four inches or more to sea level rise.

The details are complicated. Nearly all of Greenland’s largest glaciers that end on land move at top speeds of 30 to 325 feet a year, and their changes in speed are small because they are already moving slowly. Glaciers that terminate in fjord ice shelves move at 1,000 feet to a mile a year, but didn’t gain speed appreciably during the decade.

In the east, southeast and northwest areas of Greenland, glaciers that end in the ocean can travel seven miles or more in a year. Their changes in speed varied – some even slowed – but on average the speeds increased by 28 percent in the northwest and 32 percent in the southeast during the decade.

“There’s the caveat that this 10-year time series is too short to really understand long-term behavior,” says assistant professor of earth sciences at Ohio State University Ian Howat.

“So there still may be future events – tipping points – that could cause large increases in glacier speed to continue. Or perhaps some of the big glaciers in the north of Greenland that haven’t yet exhibited any changes may begin to speed up, which would greatly increase the rate of sea level rise.”