Astronomers have known for some time that the earliest galaxies were much smaller than the impressive spiral and elliptical entities which now fill our universe.

Indeed, over the lifetime of the cosmos, galaxies have put on a great deal of weight but their food, and eating habits, remain somewhat enigmatic. As such, the ESO recently kicked off a survey that focuses on galaxies during their “teenage years” – roughly the period from about 3 to 5 billion years after the Big Bang.

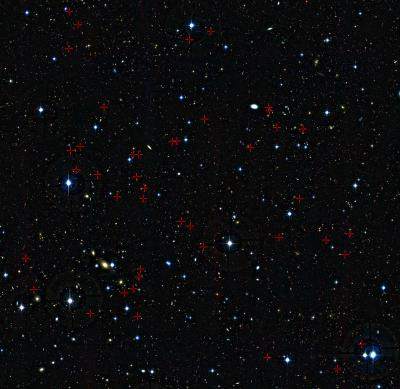

Using the ESO’s Very Large Telescope, an international team of astronomers has already collected the biggest ever set of detailed observations of gas-rich galaxies at various early stages of development.

“[There] are two different ways growing galaxies are competing,” explained Thierry Contini of IRAP, in Toulouse, France. ”Violent merging events when larger galaxies eat smaller ones, or a smoother and continuous flow of gas onto galaxies. Both can lead to lots of new stars being created.”

According to Contini, the new results point toward a significant change in the cosmic evolution of galaxies, when the Universe was between 3 and 5 billion years old. For example, smooth gas flow (eso1040) seems to have been a big factor in the building of galaxies in the very young Universe, whereas mergers subsequently became more important.

“To understand how galaxies grew and evolved we need to look at them in the greatest possible detail,” said Contini. “The SINFONI instrument on ESO’s VLT is one of the most powerful tools in the world to dissect young and distant galaxies. It plays the same role that a microscope does for a biologist.”

To be sure, distant galaxies like the ones in the survey are just tiny faint blobs in the sky, but the high image quality from the VLT used with the SINFONI instrument allows astronomers to map how different parts of the galaxies are moving and what they are made of.

“For me, the biggest surprise was the discovery of many galaxies with no rotation of their gas. Such galaxies are not observed in the nearby Universe. None of the current theories predict these objects,” Contini noted. “We also didn’t expect that so many of the young galaxies in the survey would have heavier elements concentrated in their outer parts – this is the exact opposite of what we see in galaxies today.”