Cellphones could soon contain an ultra-high-resolution microscope alongside the ubiquitous camera, thanks to a breakthrough by Michigan Technological University professor Durdu Guney.

Such a superlens would make a virus visible in a drop of blood, resolving objects as small as 100 nanometers across.

Optical lenses are limited by the so-called diffraction limit, which means that even the best can’t generally cope with anything smaller than 200 nanometers across.

Scanning electron microscopes can go right down to a nanometer, but are expensive, large and heavy.

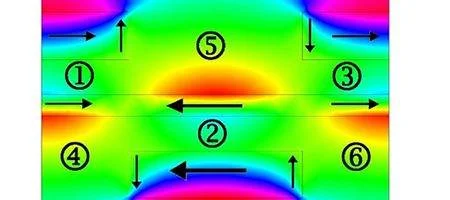

Guney’s technique is based on metamaterials. When plasmons – charge oscillations near the surface of thin metal films that combine with special nanostructures – are excited by an electromagnetic field, they gather light waves from an object and refract it in a way not seen in nature called negative refraction.

This lets the lens overcome the diffraction limit. And, unlike other techniques, it works throughout the entire spectrum of visible light. Metamaterials can be ‘stretched’ to refract light waves from the infrared all the way through visible light and into the ultraviolet spectrum.

The discovery could be applied to lithography, the microfabrication process used in electronics manufacturing.

“The lens determines the feature size you can make, and by replacing an old lens with this superlens, you could make smaller features at a lower cost. You could make devices as small as you like,” says Guney.

More entertainingly, says Guney, the superlens would be small and inexpensive anough to be readily included in devices such as smartphones.

“The public’s access to high-powered microscopes is negligible,” he says. “With superlenses, everybody could be a scientist. People could put their cells on Facebook. It might just inspire society’s scientific soul.”