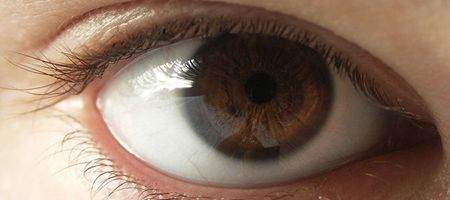

A huge computational analysis has revealed that opsins – the light-sensitive proteins key to vision – may have evolved earlier than previously believed.

Opsins are a vital component of the visual pigments that trap light in the eyes, and there’s long been intense debate over exactly when they first evolved.

To try and settle the question, the University of Bristol analysis incorporated all available genomic information from all relevant animal lineages, including a newly sequenced group of sponges called Oscarella carmela and the Cnidarians, a group of animals widely thought to have possessed the world’s earliest eyes.

Using this information, the researchers developed a timeline for the evolution of opsins, and found that an opsin ancestor common to all groups appeared some 700 million years ago.

While it was was initially considered ‘blind’, it nonetheless underwent key genetic changes over the span of 11 million years that gave it the ability to detect light, and thus enable vision.

“The great relevance of our study is that we traced the earliest origin of vision and we found that it originated only once in animals,” says Dr Davide Pisani.

“This is an astonishing discovery, because it implies that our study uncovered, in consequence, how and when vision evolved in humans.”