While it’s long been known that large herbivores like Diplodocus got through enormous amounts of plants, their exact eating habits have remained unknown.

But by using CT scans and biomechanical modelling – more usually used to design racing cars and aeroplanes – researchers say they now understand how plant-eating dinosaurs fed 150 million years ago.

It seems that Diplodocus’ skull, with its long snout and protruding peg-like teeth restricted to the very front of its mouth, was perfectly adapted to strip leaves from tree branches.

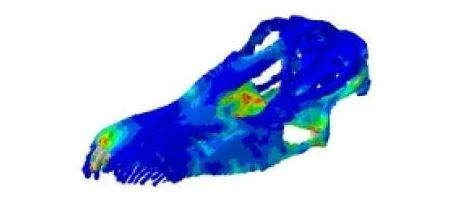

To solve the mystery, researchers from the University of Bristol and the Natural History Museum created a 3D model of a complete Diplodocus skull using data from a CT scan. This model was then biomechanically analysed to test three feeding behaviours using finite element analysis (FEA).

This revealed the various stresses and strains acting on the dinosaur’s skull during feeding, to determine whether the skull or teeth would break under certain conditions.

“Sauropod dinosaurs, like Diplodocus, were so weird and different from living animals that there is no animal we can compare them with,” says Dr Mark Young.

“This makes understanding their feeding ecology very difficult. That’s why biomechanically modelling is so important to our understanding of long-extinct animals.”

Several different hypotheses of feeding behaviour have been suggested for Diplodocus since its discovery over 130 years ago. These ranged from standard biting, combing leaves through peg-like teeth, ripping bark from trees like some living deer, and even plucking shellfish from rocks.

The team found that whilst bark-stripping was – perhaps unsurprisingly – too stressful for the teeth, combing and raking of leaves from branches was overall no more stressful to the skull bones and teeth than standard biting.

“Using these techniques, borrowed from the worlds of engineering and medicine, we can start to examine the feeding behaviour of this long-extinct animal in levels of detail which were simply impossible until recently,” says Dr Paul Barrett of the Natural History Museum.